|

Home |

A gentleman crusader on a cycle Vijay Verghese on his father for The Doon School Old Boys' Society's The Rose Bowl magazine, Jan 2015

My father B G Verghese, known simply as George – and to his extended family in Kerala as Boobli (or baby) – passed away on 30 December, 2014, ending a rich and remarkable life lived ‘without regrets’. Growing up I rarely saw him. He belonged to that post-independence tribe of nation builders for whom ‘family’ meant every underprivileged and disenfranchised person in the country. Buried under newspapers each morning as he scribbled notes and circled incorrect text, he was a formidable man to approach and one of few words. The most he seemed to say was, “Hmm,” which animated my mother no end. He led by example rather than verbose instruction and we watched carefully for clues. Yet he was always accessible – and to all. My father believed in joint responsibility and, as children, both my brother and I got our hands smacked for the other’s misdeeds. Truly was I my brother’s keeper. And he mine. There were no arguments at home. The one time I got a modest spank was for borrowing a superhero comic when I was 10. This went against his injunction, ‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be,’ but I believe it had more to do with his fear that comics would corrupt my English entirely and reduce my vocabulary to THWACK, POW, and WHAM! He had a wry wit and chuckled when he found my brother and I in his rattling cupboard one evening, apparently headed for Mars. The nascent Indian Space program was alas dismantled and my father’s Cambridge ties preserved for posterity. Simplicity was his credo. So when he contested the elections post-Emergency in 1977 he chose as his emblem, the humble cycle. He brushed aside my collegiate attempts to build a ‘brand’ for him. After all, this was the common man’s transport. While at the Indian Express, he sometimes cycled to work, often in tar-melting Delhi summer heat, causing cars to screech to a halt as startled junior journalists scrambled to give him a lift. He would have none of it. When I headed off on my first teen date, he saw me off, on a cycle. I asked him once who the most formative people in his life were and, without hesitation, he replied, his grandfather Dewan Bahadur Dr V Verghese, much loved and feted by the Mahajarah of Cochin, and great patriarch of a vast Syrian Christian family. Then there was Arthur Foot, the first headmaster of The Doon School who decided that the crisp Himalayan air and wooded valleys offered the perfect setting in which to fashion young souls steeped in their own culture but brought up in much the manner of an Eton or a Harrow. And it was Doon that really created the man who was to become my father with his eclectic blend of Gandhian principles, Christian values, Buddhist abstemiousness, spirit of adventure, and the best of liberal democratic traditions.

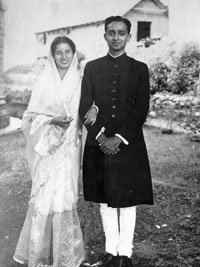

He aimed high but kept a low profile, he outlined bold strokes but explained them in simple terms, he fought the good fight with righteous indignation but never raised his voice in anger or malice, and he never compromised on his integrity. In the Sixties he toured the country to see firsthand the emergence of modern India as seen through its Nehruvian ‘temples’ of industry and mega dams. The results of this pilgrimage were contained in his 1965 book Design for Tomorrow. I asked him what his main takeaway from this exercise was and he said, simply, “The enormous diversity of India.” It was something he fought lifelong to preserve and protect. It was the core DNA of a united India. Quoted in a recent BBC interview on The Doon School, he said Foot reminded the boys they were an elite but there was no place for elitism as they were committed to the “service of those less fortunate than you.” No doubt following this exhortation, at Hindustan Times he had the paper adopt the village Chhatera as a novel experiment in developmental journalism. Humble and self-effacing, he practically wrote himself out of his memoir and I had a struggle on my hands to convince him to run his portrait on the cover. So understated was he I may well have ended up with a different father. When my mother was offered a scholarship to the USA, my father moved his courtship into high gear by asking her, “Have you considered any other alternatives?” “Like what?” she enquired. “Like me,” he blushingly responded. And that was the beginning of a great friendship and union that lasted unbroken for over 60 years. They were inseparable, my mother always distinct with a colourful flower in her hair, her sense of drama and fun a wonderful counterpoint to my father’s quiet resolve. Tribal uplift and the emancipation of women concerned him greatly as did the socio-economic liberation of the Northeast. While down with Dengue and recovering at home he awoke, fevered, at 5am one morning and bemoaned the plight of women in the country. This far outranked the searing joint and muscle aches. He was not a hugely religious person but was a man of Faith with unshakeable moral certitude. He had a rich baritone, forged at the Trinity College Cambridge choir that gave beautiful shape to gospels, Paul Robeson classics, and his signature ‘Danny Boy’ that we hope sends him on his way…

And I shall hear tho' soft you tread above me |

||||

| back to the top | |||||

HOME | ABOUT THE AUTHOR | LIST OF ARTICLES | CONTACT | BOOKS See also AsianConversations.com 11-C Dewan Shree Apartments, 30 Ferozeshah Rd, New Delhi 110001, India

|